Ratification of the 19th Amendment on August 26 1920 Gives Women the Right to Vote

Part 7 in 8 of the Suffragists Legacy Series Honoring Women's Right to Vote

Herself360 continues to participate with Suffrage100Ma in commemorating the upcoming 100th Anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, which states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

The journey for women’s rights was difficult and complicated and is not done; the work continues.

Below are very short Biographies of Influential Suffragists who fought for the right to vote.

Please check out https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/women-who-fought-for-the-vote-1 for more information about these legendary women who made it possible 100 years ago, for women to have the right to vote.

19th Amendment

19th Amendment

Susan B. Anthony did not live to see the consummation of her efforts to win the right to vote for women. She died at the age of 86 in 1906. She showed her strength and optimism until the end. Her final public utterance was, “Failure is impossible.” She and Stanton had been succeeded as heads of the suffrage movement by Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt.

A change was taking place in public perception of the movement. In the nineteenth century, social critic Orestes Bronson echoed the fears of a sufficiently large, even if hysterical, segment of the population when he warned that women’s suffrage would bring about “the destruction of the family.”

By the early twentieth century, suffragists had successfully convinced an increasing number of people that the interests of the family itself extended beyond the four walls of the home and had to be protected in public by voting wives and mothers. They claimed that women would bring a purifying influence to politics and public life.

William Howard Taft had cautiously told women to collect more signatures on their petitions before he would take up their cause. Theodore Roosevelt did not include women in his ‘progressive” campaign of 1912. Neither did Woodrow Wilson on his agenda. When the latter president ran for re-election in 1916 on the slogan “He kept us out of the war,” suffragists retorted “He kept us out of suffrage.” Female demonstrators surrounded the White House in 1917. They were arrested on a charge of obstructing traffic. When jailed, they asserted the rights of political prisoners and went on a hunger strike.

William Howard Taft had cautiously told women to collect more signatures on their petitions before he would take up their cause. Theodore Roosevelt did not include women in his ‘progressive” campaign of 1912. Neither did Woodrow Wilson on his agenda. When the latter president ran for re-election in 1916 on the slogan “He kept us out of the war,” suffragists retorted “He kept us out of suffrage.” Female demonstrators surrounded the White House in 1917. They were arrested on a charge of obstructing traffic. When jailed, they asserted the rights of political prisoners and went on a hunger strike.

The suffrage amendment was reintroduced by Jeannette Rankin of Montana on January 20, 1918. She herself was from the first region to grant the vote to women and was the first woman to be elected to Congress. The amendment passed amidst the cheers of women who sat knitting in the galleries. Other women gathered on the steps of Capitol were described by the New York Times as “cheering like collegians after a football victory.”

The vote was indeed close, only one more than the required two-thirds. One congressman left the deathbed of his suffragist wife to cast his vote and then returned to her funeral. Two congressmen came from hospitals to cast affirmative votes. Tennessee was the thirty-sixth state to ratify the amendment. On August 26, 1920, the final passage was achieved. Times had changed.

Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906)

Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906)

For over 50 years, Susan B. Anthony was the leader of the American woman suffrage movement. Born in Adams, Massachusetts on February 15, 1820, Anthony lived for many years in Rochester. In 1872 Anthony was arrested for voting. When she died in 1906, only four states allowed women to vote, but Anthony’s single-minded dedication to the cause of suffrage was largely responsible for the passage of the nineteenth amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920, giving women the vote.

Mathilde Franziska Anneke (1817–1884)

Mathilde Franziska Anneke was an entrepreneur, lecturer, educator, journalist, writer, and newspaper editor. She founded the first women’s newspapers in the German lands and in the United States and is considered the most famous woman among the German “Forty-Eighters” who immigrated to the U.S. in the mid-nineteenth century. She displayed a lifelong commitment to equal rights for women and joined the emerging Women’s Rights Movement in the United States, becoming well known by the early leading feminists living in the northeast including Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Alice Stone Blackwell (1857–1950)

Alice Stone Blackwell (1857–1950)

After graduating from Boston University in 1881, Alice Stone Blackwell, the daughter of Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, began working on her parents’ newspaper, The Women’s Journal, and served as editor for the next thirty-five years. Blackwell was instrumental in bringing about a reconciliation between the two factions of the woman’s suffrage movement in 1890. She also served as the recording secretary of the new organization for many years. Besides her efforts for women’s rights, Blackwell was also very active in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Women’s Trade Union League, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the American Peace Society.

Antoinette Brown Blackwell (1825–1921)

Antoinette Brown Blackwell (1825–1921)

Born in Henrietta, New York, Antoinette Brown Blackwell received a bachelor’s degree from Oberlin College in 1847 and then, much to the consternation of the college, applied to study theology. Although she finished the requirements for the program in 1850, Oberlin did not allow her to graduate. Undeterred, she was ordained in 1853 as minister of the First Congregational Church in Butler and Savannah, Wayne County, New York, and thus became the first ordained woman minister of a recognized denomination in the United States.

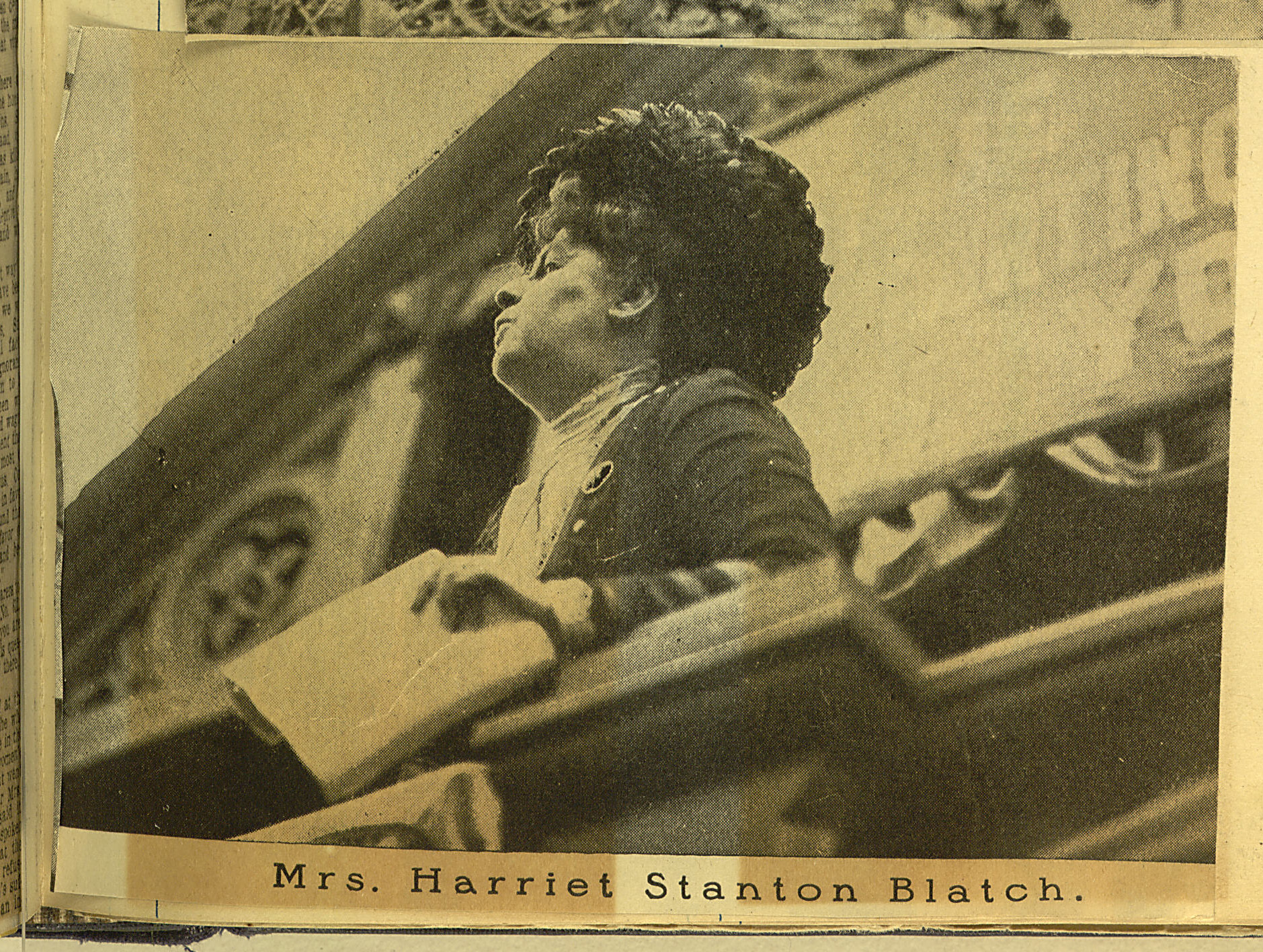

Harriet Stanton Blatch (1856–1940)

Harriet Stanton Blatch (1856–1940)

The daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriet Stanton Blatch carried on her mother’s work as one of the leaders of the woman suffrage movement. After marrying an Englishman in 1882, Blatch lived in England for twenty years, returning to the United States in 1902. In 1908 she founded the Women’s Political Union. Patterned after organizations Blatch had known in England, the Union—sometimes to the discomfort of more conservative suffragists—fostered close ties with working-class women and employed such tactics as massive parades and active political campaigning.

Amelia Bloomer (1818–1894)

In 1849 Amelia Bloomer began publishing a temperance newspaper, The Lily, in Seneca Falls, New York. Presently, the paper began to publish articles on women’s rights as well as temperance. In the winter of 1850-51 Bloomer wrote an article defending the pantaloons and short skirt worn by the dress reformer Elizabeth Smith Miller against the fashionable, constricting clothes worn by women. Several feminists, including Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucy Stone, wore what became known as the “bloomer” until ridicule forced them to return to more traditional garb.

Carrie Chapman Catt (1859–1947)

Carrie Chapman Catt (1859–1947)

After graduating from Iowa State College in 1880, Carrie Chapman Catt pursued a brief career as educator, journalist, and lecturer. After attending her first national suffrage convention in 1890 as a delegate from Iowa, Catt quickly rose to the top ranks of the suffrage movement. When Susan B. Anthony retired from the presidency of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1900, she chose Catt as her successor. Forced to resign in 1904 because of her husband’s failing health, Catt again became president of the NAWSA in 1915 and led the suffrage cause to victory in 1919. She was also the leader of the international suffrage organization and the peace movement. With the vote won, Catt founded the League of Women Voters to educate women on political issues and served as the organization’s honorary president until her death in 1947. She published a history of suffrage in 1923, Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement. She also gave her attention to other issues such as child labor and world peace. After the horrors of World War I, she organized the Committee on the Cause and Cure of War (1925). Concerned about Hitler’s growing power, she worked on behalf of German Jewish refugees and was awarded the American Hebrew Medal (1933).

Julia Ward Howe (1819–1910)

Julia Ward Howe (1819–1910)

Best known as the author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” Julia Ward Howe was also a leading suffragist and a pioneer in the women’s club movement. After the war, an active clubwoman, Howe established and led major women’s organizations. She championed the vote for women, helping to found the New England Suffrage Association in 1868, as well as the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) divided over whether to support the 15th Amendment, which promised voting rights for black men but not all women. Howe joined Lucy Stone in founding the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which championed the Fifteenth Amendment, and broke with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s NWSA. Howe also helped establish the AWSA’s newspaper, the Woman’s Journal, which she edited for 20 years. In 1889, the groups reunited as the National American Woman Suffrage Association with the singular goal of votes for women.

Howe also became a peace advocate, presiding over the Women’s International Peace Association in 1871. Known as the “Dearest Old Lady in America,” she lectured widely, particularly for the Unitarian Church, founding clubs wherever she went. In 1873, she organized the Association for the Advancement of Women to improve women’s education and entry into the professions.

Lucretia Coffin Mott (1793–1880)

Lucretia Coffin Mott (1793–1880)

Lucretia Mott was a Quaker minister, abolitionist, and pioneer in the women’s rights movement. In 1840 she traveled to London with her husband James Mott as a delegate to the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention. At the convention, the women delegates were refused recognition and not allowed to participate in the proceedings. Grieved by this treatment, Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was also attending the anti-slavery convention, determined to hold a meeting to discuss the rights of women. Mott, Stanton, and Mott’s sister, Martha Coffin Wright, organized and called together the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York in July of 1848. Throughout her long life, Mott continued to work for the rights of women and for freed blacks after the Civil War.

Anna Howard Shaw (1847–1919)

In 1878 Anna Howard Shaw graduated from Boston University with a degree in theology. In 1880 she was ordained by the Methodist Protestant Church, becoming that denomination’s first woman minister. In 1883 she enrolled in the medical school of Boston University and earned an M.D. degree in 1886. Shaw soon came to believe, however, that neither religion nor medicine could solve basic social problems, particularly those of women. After meeting Susan B. Anthony in 1888, she devoted her oratorical talents full-time to the woman suffrage cause and served as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1904 to 1915. While Shaw died just before the Women’s Suffrage Amendment was ratified, she fulfilled her vision of success: “Nothing bigger can come to a human being than to love a great cause more than life itself.”

Widely credited as one of the founding geniuses of the women’s rights movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton used her brilliance, insightfulness, and eloquence to advocate for many important issues. In 1840, Elizabeth Cady Stanton accompanied her husband Henry to the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London, England. When the British excluded from the convention the American women delegates, including Lucretia Mott, Stanton and Mott resolved to hold a women’s rights convention when they returned to the United States. In 1848, the first such convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York, where Stanton was then living. The Declaration of Sentiments that Stanton drafted for the convention enumerated eighteen legal grievances suffered by women, including lack of the franchise and the right to their wages, their person, and their children. It also called attention to women’s limited educational and economic opportunities. In 1851, Stanton met Susan B. Anthony and for the next fifty years, they worked in close collaboration, Stanton articulating the arguments for improving the legal and traditional rights of women, and Anthony organizing and campaigning to achieve these goals.

Lucy Stone (1818–1893)

Lucy Stone (1818–1893)

In 1843 Lucy Stone graduated from Oberlin College, which had been established ten years earlier as the first co-educational college. Stone became a lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society and an eloquent speaker on behalf of women’s rights. In 1855 she married fellow abolitionist Henry Browne Blackwell in 1855 on condition that she would retain her maiden name. After the Civil War, the suffrage movement split over tactical and policy differences, with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton founding the National Woman Suffrage Association and Stone the American Woman Suffrage Association. Beginning in 1872, Stone, Henry Blackwell, and later their daughter Alice Stone Blackwell, published the most influential women’s rights newspaper, The Woman’s Journal, for forty-seven years. In 1890 the two suffrage organizations merged, and Stone became chairman of the executive committee.

Sojourner Truth (1797–1883)

Sojourner Truth (1797–1883)

In 1843, Isabella, a former slave, changed her name to Sojourner Truth and began traveling through the eastern United States preaching the word of God. In Northampton, Massachusetts, she encountered the abolitionist movement and began traveling and lecturing on behalf of that cause. She maintained herself by selling copies of the Narrative of Sojourner Truth, which had been written by Olive Gilbert and published in 1850. After attending a women’s rights convention in 1850, Truth also became a speaker on women’s rights issues. During the Civil War, she solicited gifts of food for regiments of black volunteers, and after the war, she worked to find homes and employment for recently freed slaves.

Adapted from a publication produced for the 95/75 Celebration by Eastman Kodak Company, K2-Design—Monica Guilian, and Millennia Communications—Catherine Samson, 1995.

Information Courtesy of :

2. https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/women-who-fought-for-the-vote-1

3. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies

4. https://www.womenofthehall.org/

5. https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/R/RANKIN,-Jeannette-(R000055)/

6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucretia_Mott

7. Biography of Mathilde Franziska Anneke adapted from Richards-Wilson, Stephani. “Mathilde Franziska Anneke (née Giesler).” In Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to the Present, vol. 2, edited by William J. Hausman. German Historical Institute. Last modified June 30, 2014.

8. I am not my Gender: Early Women's Suffrage https://xtinem.com/i-am-not-my-gender-early-womens-suffrage-pioneer-lucretia-mott/99

9. All others adapted from biographies prepared by Mary M. Huth, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Rochester Libraries, February 1995.