Women! Your Right to Vote has an Amazing History.

Herself360 looks forward to participating with Suffrage100Ma in commemorating the upcoming 100th Anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, which states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Herself360 looks forward to participating with Suffrage100Ma in commemorating the upcoming 100th Anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, which states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

The journey for women’s rights was difficult and complicated and is not done; the work continues.

1Women first organized and collectively fought for suffrage at the national level in July of 1848. Suffragists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott convened a meeting of over 300 people in Seneca Falls, New York. In the following decades, women marched, protested, lobbied, and even went to jail. By the 1870s, women pressured Congress to vote on an amendment that would recognize their suffrage rights. This amendment was sometimes known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment and became the 19th Amendment.

2On Saturday, May 2, 1914, American women from all across the country participated in a well-coordinated set of suffrage parades and meetings. A visit to Washington, DC was planned for the following Saturday, May 9, so that the various groups could present to Congress their petitions in support of a Federal suffrage amendment.

Boston was the location for one of the largest parades (and the first suffrage parade that had ever been held in Massachusetts). Various estimates put the number of marchers at somewhere between 9,000-15,000, and the number of spectators at 200,000-300,000. The crowd had been building all day--pouring into the city on trolleys and trains, carrying blankets and picnic lunches, and camping out on Back Bay doorsteps and on the Common until they took up their places all along the parade route by 4 p.m.

Chief Marshal Frances Curtis led the parade on horseback along with eight mounted aides. The mile-long parade was a sea of white dresses adorned with yellow jonquils, narcissus, paper roses, badges, and ribbons. Over 800 policemen had been assigned to keep order at the parade, and streetcars were diverted from the parade route.

Chief Marshal Frances Curtis led the parade on horseback along with eight mounted aides. The mile-long parade was a sea of white dresses adorned with yellow jonquils, narcissus, paper roses, badges, and ribbons. Over 800 policemen had been assigned to keep order at the parade, and streetcars were diverted from the parade route.

At 5 p.m., down Beacon Street from Massachusetts Avenue they came, well-known suffragists and college girls, elaborate floats, 13 bands, two hundred automobiles, and contingents of male supporters. The temperature was in the low sixties, and the weather sunny and breezy; the women marched with a noted seriousness of purpose.

They passed in review before Governor Walsh and Lt. Governor Barry, who stood at attention in top hats and overcoats on the State House on Beacon Hill, under the gleaming gold dome. (Former mayor "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald, John F. Kennedy's grandfather, was also present on the State House steps.) They then passed before Mayor and Mrs. Curley who awaited them in front of City Hall.

The parade marchers then looped around the business district and returned to conclude at the Tremont Temple.

The opening division of the parade included well-known suffragists--both local and national. Alice Stone Blackwell, daughter of well-known abolitionist and suffragist Lucy Stone, and a prominent suffragist in her own right, was one of the leaders.

Local artist and Smith College graduate Blanche Ames Ames, who had worked since 1903 providing beautiful illustrations for her husband's seven-volume study of orchids, marched with the parade committee. (Her husband was Harvard botany professor Oakes Ames who also marched in the parade--but in a different division.) In 1915, Blanche would produce a widely noted series of suffrage cartoons, and the following year, in 1916, she would go on to co-found the Massachusetts Birth Control League.

Thirty ushers marched wearing red and white striped gowns, and blue caps and shoulder capes. Representatives of countries where women already had the vote (or at least partial suffrage) marched in their national costumes; according to the Boston Sunday Globe, the "Finnish and Galician peasants" marched "with their hair unbound and floating free."

Thirty ushers marched wearing red and white striped gowns, and blue caps and shoulder capes. Representatives of countries where women already had the vote (or at least partial suffrage) marched in their national costumes; according to the Boston Sunday Globe, the "Finnish and Galician peasants" marched "with their hair unbound and floating free."

The second division included women from 80 Massachusetts cities and towns. The women from Concord and Lexington were accompanied by "Spirit of '76" musicians. Fifty Brookline women rode on horseback. One contingent of women carried a banner that read: "It takes a woman to make a flag."

The third division was headed by the Junior Suffrage League, led by Louis Brandeis' daughter Elizabeth, who would start on the path to her long and illustrious career in economics and labor law as a Radcliffe student that September. (Her father would be named to the Supreme Court while she was still in college.) Self-supporting women came next, and then the professional women starting with stenographers and business women, then architects and artists, doctors and dentists, lawyers, musicians, nurses, teachers, writers, and actresses. Doctors and lawyers wore caps and gowns.

"Self-supporting women" included Margaret "Maggie" Foley, an outspoken Irish Catholic who'd joined the Hat Trimmers' Union, started organizing women workers in a hat factory, become a well-known labor organizer, and had started working for the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association in 1906. She was known as "The Grand Heckler", and the applause that greeted her appearance, as she stood in the middle of a touring car, holding an immense red rose in her left hand and waving a white scarf with her right, was thunderous. (The red rose was the symbol of the anti-suffragists; she was clearly taunting them!)

Artists marching included sculptor Anne Whitney, whose statue of Sam Adams adorns Statuary Hall at the Capitol Building in Washington. Anne was 93, and still active in the arts. She had been a well-known abolitionist in the pre-Civil War era, and, like many women abolitionists, had turned her attention to freedom for women after the War. (She would die less than eight months later, leaving $1,000 in her will to Alice Stone Blackwell "for use in the suffrage movement.")

Artists marching included sculptor Anne Whitney, whose statue of Sam Adams adorns Statuary Hall at the Capitol Building in Washington. Anne was 93, and still active in the arts. She had been a well-known abolitionist in the pre-Civil War era, and, like many women abolitionists, had turned her attention to freedom for women after the War. (She would die less than eight months later, leaving $1,000 in her will to Alice Stone Blackwell "for use in the suffrage movement.")

Lawyers included Alice Parker Lesser, who had been admitted to the bar in Massachusetts in 1890--the first year women were allowed entry.

Writers were accompanied by Charlotte Payne-Townshend, George Bernard Shaw's wife.

The fourth division included clubs, unions, and associations, the Massachusetts Men's League for Woman Suffrage, the College Men's Suffrage League (including 500 male Harvard students), college faculty members (women and men) in caps and gowns, and undergraduate women from Mount Holyoke, Radcliffe, Simmons, Smith, Wellesley, MIT, Tufts, and Boston University. (The last three were coeducational by this time; BU had been the first university in the U.S. to open all of its programs to women.)

The sun set at 6:45 p.m., but still, the marchers came; it was past 7 by the time the parade wrapped up. Then many of the marchers headed to the Tremont Temple for sandwiches and a program of speakers and ceremonies.

The write-up in the next day's Boston Sunday Globe, entitled "Women Give Great Parade" was the front-page story. The sub-heads tell it all: "Nearly 12,000 in Striking Appeal for Ballot." "Earnest Marchers Win Favor with Surging Crowds." "Finish at Tremont Temple Rally in Spirit of Exaltation."

Information from this Post was received from:

1. https://www.nps.gov/articles/massachusetts-and-the-19th-amendment.htm

2. http://boston1905.blogspot.com/2009/07/boston-suffrage-parade-may-2-1914.html

3. https://www.wbur.org/artery/2020/02/20/documentary-borderland-blanche-ames-suffragette-activist

Poster Photos are

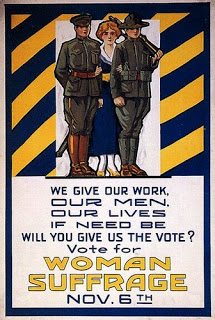

1. American World War One era poster designed by Evelyn Rumsey Cary, a Buffalo, NY artist.

2. Poster from a 1917 New York suffrage campaign.